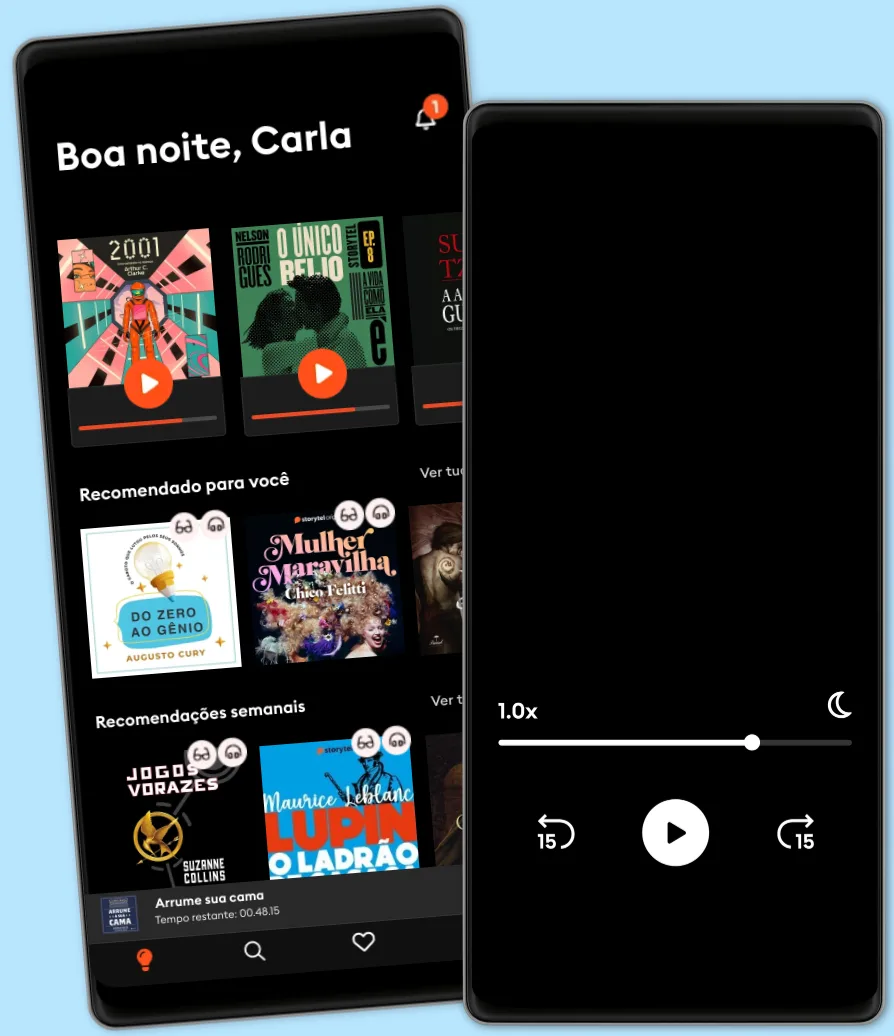

Ouça e leia

Entre em um mundo infinito de histórias

- Ler e ouvir tanto quanto você quiser

- Com mais de 500.000 títulos

- Títulos exclusivos + Storytel Originals

- 7 dias de teste gratuito, depois R$19,90/mês

- Fácil de cancelar a qualquer momento

The End of the Julio-Claudian Dynasty in Rome: The History of Nero’s Reign and the Year of the Four Emperors

- Editor

- Idioma

- Inglês

- Formato

- Categoria

História

Throughout the annals of history, there have been few figures as reviled as Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, better known as Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus, or more simply, Nero. Even today, he remains one of the Roman Empire’s most famous – or notorious – figures, a villain whose impact on popular culture is so vast that his name crops up consistently to this day in literature, film, TV and mediums as unlikely as video games and anime.

Nero ranks among the very worst of the Caesars, alongside the likes of mad Caligula, slothful Commodus, and paranoid Domitian, a figure so hated that, in many ancient Christian traditions, he is literally, without hyperbole, considered the Antichrist; according to a notable Biblical scholar, the coming of the Beast and the number 666 in the Book of Revelation are references to Nero. He was the man who, famously, “fiddled while Rome burned”, an inveterate lecher, a murderous tyrant who showed little compunction in murdering his mother and who liked to use Christian martyrs as a source of illumination at night – by burning them alive. His economic policies, according to many historians, virtually bankrupted Rome.

Even his appearance, apparently, was ill-favoured. His busts show him to be fleshy-faced, with a weak chin that he attempted to disguise with a distinctly unprepossessing beard, and according to Suetionius he was also spotty, stinking, pot-bellied and thin-legged – not a pretty picture.

The best known accounts of Nero come from biographers like Tacitus, Cassius Dio, Suetionius and Josephus, but there are also indications that, to some extent, reports of Nero’s cruelty were exaggerated. Nero was popular with the common people and much of the army, and during his reign the Empire enjoyed a period of remarkable peace and stability. Many historians, including some of his ancient biographers – such as Josephus – suggest that there existed a strong bias against Nero. Part of this is because his successors wished to discredit him, and justify the insurrections which eventually drove him, hounded from the throne, to a lonely suicide. Much of the bias against Nero can also be attributed to the fact that he was a renowned persecutor of Christians, and since many of the historians who wrote about Nero in the years after his death were Christians themselves, it made sense for them to have a jaundiced view of their erstwhile nemesis. Because of this, some historians have suggested that Nero’s demeanour and reputation might not be as black as the original sources might be inclined to suggest.

Having left no heir, Nero’s death plunged the empire into confusion and chaos, bringing to an end the Julio-Claudian lineage while at the same time offering no clear rule of succession. This presented the opportunity for influential individuals in the empire, and in particular provincial governors who also commanded large military garrisons, to express and further their own ambitions to power. The result was a period of instability and civil war as several pretenders to the throne, among them the emperors Galba, Otho and Vitellius, gained and lost power, until finally the emperor Vespasian seized and retained the imperial principate. Vespasian imposed order and discipline on a chaotic empire and founded the Flavian Dynasty, which survived until CE 96, encompassing the reigns of Vespasian himself (69–79), and his two sons Titus (79–81) and Domitian (81–96).

© 2025 Charles River Editors (Ebook): 9781475332285

Data de lançamento

Ebook: 1 de maio de 2025

- Pratique o poder do "Eu posso" Bruno Gimenes

4.5

- 18 Maneiras De Ser Uma Pessoa Mais Interessante Tom Hope

4

- O sonho de um homem ridículo Fiódor Dostoiévski

4.7

- Gerencie suas emoções Augusto Cury

4.5

- 10 Maneiras de manter o foco James Fries

3.8

- Harry Potter e a Pedra Filosofal J.K. Rowling

4.9

- Os "nãos" que você não disse Patrícia Cândido

4.2

- A gente mira no amor e acerta na solidão Ana Suy

4.5

- A metamorfose Franz Kafka

4.4

- Mais esperto que o diabo: O mistério revelado da liberdade e do sucesso Napoleon Hill

4.7

- Jogos vorazes Suzanne Collins

4.8

- A arte da guerra Sun Tzu

4.6

- Primeiro eu tive que morrer Lorena Portela

4.3

- talvez a sua jornada agora seja só sobre você: crônicas Iandê Albuquerque

4.5

- O Último Desejo Andrzej Sapkowski

4.8

Português

Brasil